BSidesCBR 2025 CTF (skateboarding dog) - rev writeups

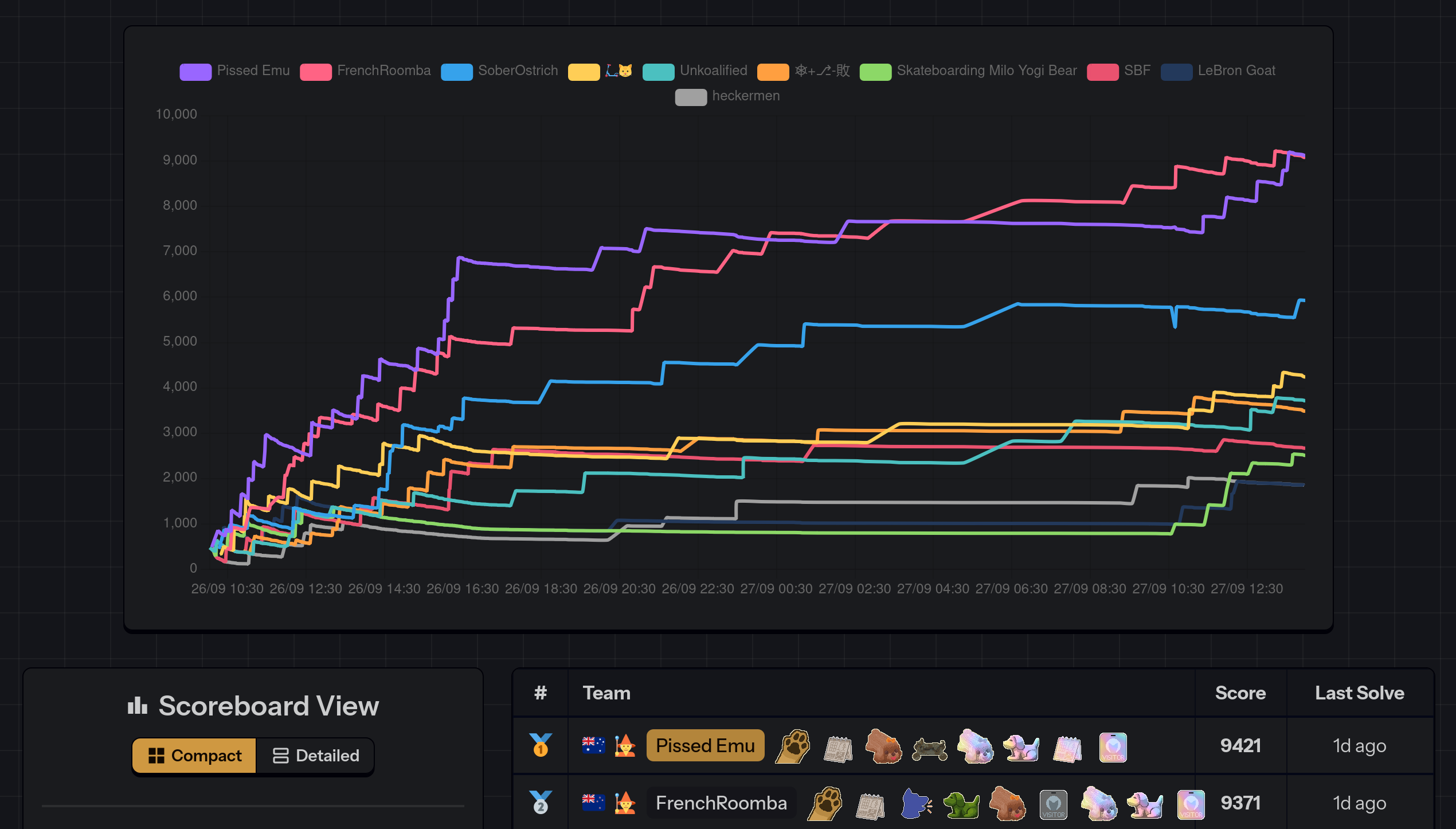

At BSidesCBR 2025 I participated in the CTF competition organised by the team skateboarding dog, the winners of the CTF from the previous year. My team, Emu Exploit (a.k.a. PissedEmu), barely eked out a win by 50 points.

The Winged Thong of Hermes

The winged thong of Hermes has had a plugger blowout! Can you help him manage his flipflops??

Provided was main.hbc, a Hermes bytecode file. Immediately, I moved to use hermes-dec, authored by P1 Security, and decompiled the code.

Immediately, I recognised the use of a modified version of JavaScript Obfuscator from the below excerpted decompiled code:

r2 = function() { // Original name: function-name-stripped, environment: r1

r2 = undefined;

var _closure1_slot0 = r2;

r2 = ['1346688GsYqBF', '642600OGAjyU', '51124tOZNVC', '4990118ZwmYOo', '2740428WkIhlO', '1040759GmWMSJ', '249GyPWlg', '5191686RfXSRp', '16xjFwvS'];

_closure1_slot0 = r2;

r1 = function() { // Original name: function-name-stripped, environment: r1

r1 = _closure1_slot0;

return r1;

};

r2 = global;

r2['a0_0x4af0'] = r1;

r1 = global;

r1 = r1.a0_0x4af0;

r2 = undefined;

r3 = r2;

r1 = r3[r1](r2);

return r1;

};

r5 = function(a0, a1) { // Original name: function-name-stripped, environment: r1

_fun5: for(var _fun5_ip = 0; ; ) switch(_fun5_ip) {

...

r0 = global;

r3 = r0.parseInt;

r4 = _closure1_slot3;

r0 = _closure1_slot2;

r2 = r0._0x2cdff7;

r0 = undefined;

r8 = r0;

r7 = r2;

r2 = r8[r4](r7, r6);

r0 = undefined;

r8 = r0;

r7 = r2;

r2 = r8[r3](r7, r6);

r0 = 803;

r3 = -r0;

r0 = 11;

r3 = r0 * r3;

r4 = 1;

r0 = 6775;

r0 = r4 * r0;

r3 = r3 + r0;

r0 = 2059;

r0 = r3 + r0;

r2 = r2 / r0;

The above two match the pattern of the string array function, the use of hexadecimal identifiers, and the string array rotator, and within that, the use of synthetic expressions to obfuscate numeric literal constants. Strangely, the string obfuscation isn’t used anywhere else and I haven’t run into any problems with it throughout my solve.

Additionally, the bytecode heavily uses string splitting, like in the below excerpt:

r2 = global;

r4 = r2.a0_0x553e57;

r3 = 'd';

r2 = 'e';

r3 = r3 + r2;

r2 = 'c';

r3 = r3 + r2;

r2 = 'r';

r3 = r3 + r2;

r2 = 'y';

r3 = r3 + r2;

r2 = 'p';

r3 = r3 + r2;

r2 = 't';

r2 = r3 + r2;

r3 = r4[r2];

r2 = global;

r2 = r2.a0_0x3508d0;

r8 = r4;

r7 = r2;

From the above, I immediately recognised that the flag was encrypted somewhere in this bytecode, and I further identified the potential key, IV, and ciphertext, defined in the following manner:

r2 = 1373;

r3 = -r2;

r2 = 1487;

r4 = -r2;

r2 = 4;

r2 = r4 * r2;

r3 = r3 + r2;

r2 = 7352;

r2 = r3 + r2;

r3 = new Array(48);

r3[0] = r2;

r4 = 1777;

r2 = 441;

r4 = r4 + r2;

r2 = 108;

r5 = -r2;

r2 = 20;

r2 = r2 * r5;

r2 = r4 + r2;

r3[1] = r2;

r2 = 371;

r4 = -r2;

r2 = 21;

r4 = r4 * r2;

r2 = 3004;

r2 = -r2;

r4 = r4 + r2;

r2 = 10869;

r5 = -r2;

r2 = 1;

r2 = -r2;

r2 = r5 * r2;

r2 = r4 + r2;

r3[2] = r2;

r2 = 1382;

r4 = -r2;

r2 = 1546;

r4 = r4 + r2;

r2 = 117;

r2 = -r2;

r2 = r4 + r2;

...

r2 = global;

r2['a0_0x3508d0'] = r3;

While the complex subexpressions assigned to each index of the empty array may seem daunting, remember that the decompilation is basically a literal exact translation of register-to-register operations, and that further synthetic expressions obfuscating numeric constants are generally pure, meaning it does not rely on external variables, nor does it have any side-effects. The bytearrays can be very trivially extracted using nothing but the Node.js REPL:

Welcome to Node.js v24.0.2.

Type ".help" for more information.

> r2 = 1373;

1373

> r3 = -r2;

-1373

> r2 = 1487;

1487

> r4 = -r2;

-1487

> r2 = 4;

4

> r2 = r4 * r2;

-5948

> r3 = r3 + r2;

-7321

> r2 = 7352;

7352

> r2 = r3 + r2;

31

> r3 = new Array(48);

[ <48 empty items> ]

> r3[0] = r2;

31

...

> r3

[

31, 58, 74, 47, 247, 24, 242, 11, 111,

114, 42, 131, 62, 157, 248, 213, 19, 191,

202, 16, 171, 157, 105, 199, 39, 250, 255,

126, 251, 139, 226, 221, 225, 113, 105, 72,

250, 221, 170, 31, 205, 46, 241, 176, 102,

179, 34, 142

]

With careful copy-and-pasting from the decompiled code, we can very easily extract the bytearrays like so:

...

r2 = global;

r2['a0_0x3508d0'] = r3;

console.log(_closure0_slot1)

console.log(_closure0_slot2)

console.log(global.a0_0x3508d0)

console.log(toHexString(_closure0_slot1))

console.log(toHexString(_closure0_slot2))

console.log(toHexString(global.a0_0x3508d0))

function toHexString(byteArray) {

return Array.from(byteArray, function(byte) {

return ('0' + (byte & 0xFF).toString(16)).slice(-2);

}).join('')

}

Which returns the following:

a18467440abea1da4666964872fc93cffd3c0e0fa5085c1e63b6cb34ea07887d1f3a4a2ff718f20b6f722a833e9df8d513bfca10ab9d69c727faff7efb8be2dde1716948faddaa1fcd2ef1b066b3228e

Judging from the bytearray lengths aligning to multiples of 16, it was very likely that this was a block cipher of some kind - I had guessed AES, where the first two was the key and IV, and vice versa, and the last was the ciphertext. I iterated through every block mode on CyberChef, but unfortunately no combination yielded a readable flag.

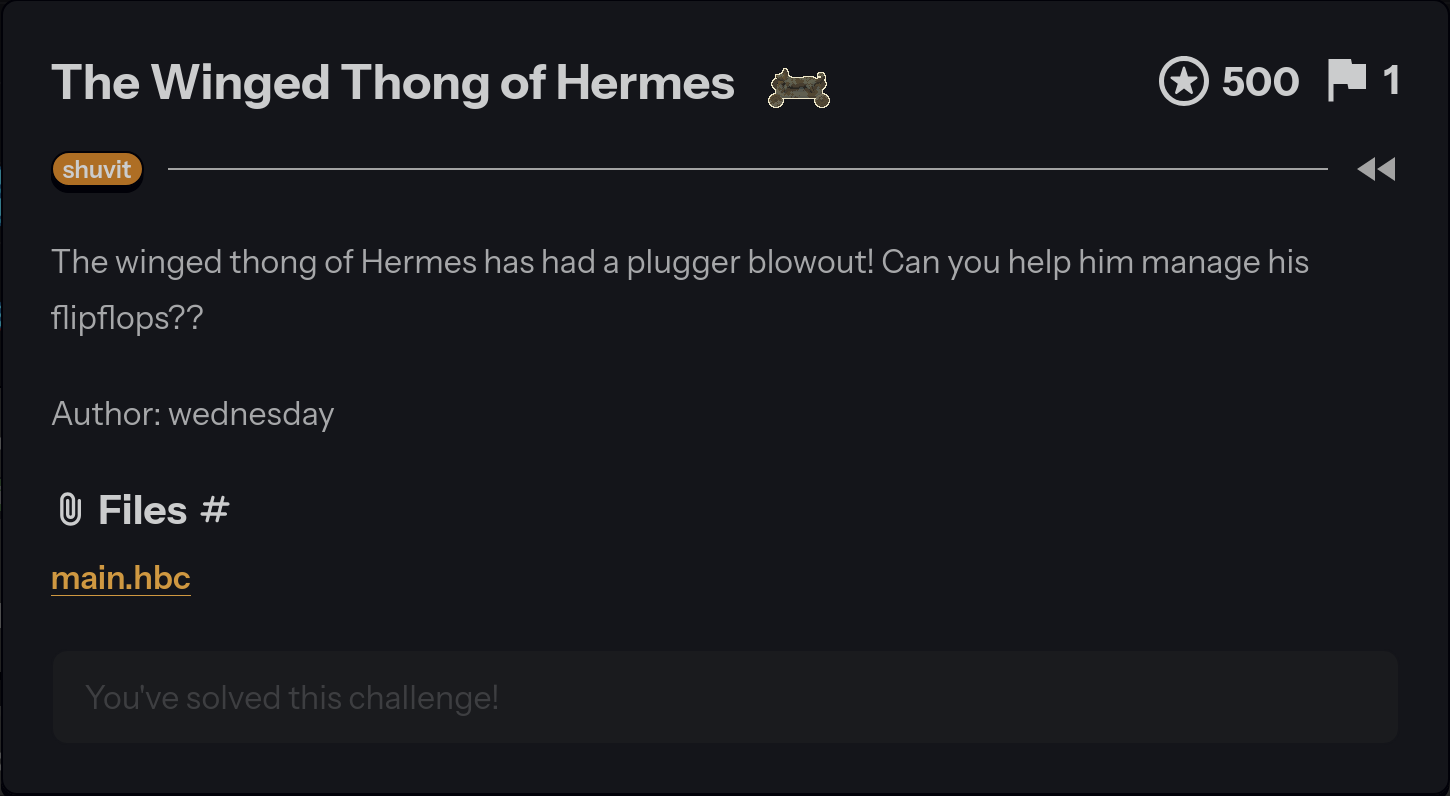

It was at this point the challenge author approached my table and I showed her the bytearrays I found - cue some slight panic from her end about an unintended solve.

Pivoting back to the bytecode, I had to recognise which library was being used, and from there I had to analyse the encryption method used.

I went back to the top-level main code and effectively hand decompiled it to the following:

global.flipflops = false;

const unknownLibrary = (function() { // Original name: function-name-stripped, environment: r1

// Module definition of some unknown library

})();

global.print('The winged thong of Hermes has had a plugger blowout! Can you help him manage his flipflops??', r6);

const key = [

161, 132, 103, 68, 10,

190, 161, 218, 70, 102,

150, 72, 114, 252, 147,

207

];

const iv = [

253, 60, 14, 15, 165, 8,

92, 30, 99, 182, 203, 52,

234, 7, 136, 125

];

global.a0_0x3508d0 = [

31, 58, 74, 47, 247, 24, 242, 11, 111,

114, 42, 131, 62, 157, 248, 213, 19, 191,

202, 16, 171, 157, 105, 199, 39, 250, 255,

126, 251, 139, 226, 221, 225, 113, 105, 72,

250, 221, 170, 31, 205, 46, 241, 176, 102,

179, 34, 142

];

global.a0_0x594467 = unknownLibrary._0x207574._0x360a8b._0x4f3932(global.a0_0x3508d0);

global.a0_0x553e57 = new unknownLibrary._0x1795e3._0x2788c7(key, iv);

global.a0_0x2b6a67 = global.a0_0x553e57.decrypt(global.a0_0x3508d0);

global.a0_0x33edf0 = unknownLibrary._0x207574._0x1ba84c._0x4f3932(global.a0_0x2b6a67);

global.print(r1.a0_0x33edf0);

Drilling into the library, I had identified where the functions were set as property values in a module object (outlined as several assignments by the obfuscator):

r1 = {};

r2 = _closure1_slot18;

r1['_0x56b49b'] = r2;

r2 = {};

r3 = _closure1_slot19;

r2['_0x2788c7'] = r3;

r1['_0x1795e3'] = r2;

r2 = {};

r3 = _closure1_slot1;

r2['_0x360a8b'] = r3;

r3 = _closure1_slot0;

r2['_0x1ba84c'] = r3;

r1['_0x207574'] = r2;

r2 = {};

r3 = {};

r4 = _closure1_slot27;

r3['pad'] = r4;

r4 = _closure1_slot28;

r3['_0x1b08ba'] = r4;

r2['_0x2ac515'] = r3;

r1['padding'] = r2;

r2 = {};

r3 = _closure1_slot23;

r2['_0x9b7a4c'] = r3;

r3 = _closure1_slot24;

r2['_0x14008a'] = r3;

r3 = _closure1_slot25;

r2['_0x5173d0'] = r3;

r1['_0x2233bb'] = r2;

_closure1_slot20 = r1;

r0 = _closure1_slot20;

return r0;

Looking further into _closure1_slot19, where what looks to be some sort of a Cipher class, we can see the following behaviour in the cleaned decompiled code:

this.description = 'dont';

this.name = 'have';

It looks like the challenge author did use a cryptography library and removed some identifying strings - however this doesn’t stop a cursory GitHub search from identifying this particular library as aes-js. From this, we can map unobfuscated names to the previous module definition using the original source file after some cleaning up.

return {

// AES

_0x56b49b: _closure1_slot18,

// ModeOfOperation

_0x1795e3:{

// ???

_0x2788c7: _closure1_slot19,

},

// utils

_0x207574: {

// hex

_0x360a8b: _closure1_slot1,

// utf8

_0x1ba84c: _closure1_slot0,

},

padding: {

// pkcs7

_0x2ac515 {

pad: _closure1_slot27,

// unpad

_0x1b08ba: _closure1_slot28,

},

},

// _arrayTest

_0x2233bb: {

// coerceArray

_0x9b7a4c: _closure1_slot23,

// createArray

_0x14008a: _closure1_slot24,

// copyArray

_0x5173d0: _closure1_slot25,

},

};

With the above mappings, we can clean up the previous top-level code:

global.a0_0x594467 = aesjs.utils.hex.fromBytes(global.a0_0x3508d0);

global.a0_0x553e57 = new aesjs.ModeOfOperation.ModeOfOperationUNK(key, iv);

global.a0_0x2b6a67 = global.a0_0x553e57.decrypt(global.a0_0x3508d0);

global.a0_0x33edf0 = aesjs.utils.utf8.fromBytes(global.a0_0x2b6a67);

global.print(r1.a0_0x33edf0);

The actual block cipher mode is still unknown, diving into the constructor (_closure1_slot19) and correlating with the usual code patterns identified in the original library source, we find that the only block mode cipher which takes a key and an IV highly aligns with ModeOfOperationCBC.

Using the exact same library, and using effectively the same code, it still failed:

const key = [

161, 132, 103, 68, 10,

190, 161, 218, 70, 102,

150, 72, 114, 252, 147,

207

];

const iv = [

253, 60, 14, 15, 165, 8,

92, 30, 99, 182, 203, 52,

234, 7, 136, 125

];

global.a0_0x3508d0 = [

31, 58, 74, 47, 247, 24, 242, 11, 111,

114, 42, 131, 62, 157, 248, 213, 19, 191,

202, 16, 171, 157, 105, 199, 39, 250, 255,

126, 251, 139, 226, 221, 225, 113, 105, 72,

250, 221, 170, 31, 205, 46, 241, 176, 102,

179, 34, 142

]

const out_cbc = new aesjs.ModeOfOperation.cbc(key, iv).decrypt(global.a0_0x3508d0);

console.log(aesjs.utils.utf8.fromBytes(out_cbc));

The challenge author approached me again; I showed her that despite half an hour of attempts, I couldn’t decrypt and she seemed confused. Anyways, I figured there must have been some weird block cipher or key derivation that I must have missed. Going back to the constructor of the ModeOfOperation, I found that it calls another internal function which I couldn’t recognise from anything found in aes-js. This function, _closure1_slot18, has several references to global.flipflops in the form of the following:

global.flipflops = !global.flipflops;

if (!global.flipflops) {

global.quit();

}

global.flipflops = ~global.flipflops;

if (!!global.flipflops) {

global.quit();

}

It was at this point that I wasted a couple of hours overthinking it and cleaning up the decompile of this unknown function before I realised I could try to execute the bytecode file itself and patch the VM runtime from there. Executing with the open-source Hermes VM runtime outputs the following:

$ ./bins/hermes main.hbc

The winged thong of Hermes has had a plugger blowout! Can you help him manage his flipflops??

Uncaught QuitError: Quit

at quit (native)

at function-name-stripped (address at main.hbc:1:208372)

at function-name-stripped (address at main.hbc:1:208044)

at function-name-stripped (address at main.hbc:1:229644)

at function-name-stripped (address at main.hbc:1:5048)

Neat, so the flag printing is stopped by global.quit, with global.flipflops as the likely predicate, as expected. Note that global.quit() isn’t a bytecode-specific functionality or exception, it just happens to be a JavaScript function installed by the runtime whose return value is also assigned to a register like any other function, but obviously is stopped before that since the VM runtime throws an exception:

r3 = global;

r4 = r3.quit;

r3 = r4.call(undefined);

r0 = r3;

What if we try to recompile Hermes with just one patch:

diff --git a/lib/ConsoleHost/ConsoleHost.cpp b/lib/ConsoleHost/ConsoleHost.cpp

index 2dc4361f2..dcaec8520 100644

--- a/lib/ConsoleHost/ConsoleHost.cpp

+++ b/lib/ConsoleHost/ConsoleHost.cpp

@@ -34,7 +34,8 @@ ConsoleHostContext::ConsoleHostContext(vm::Runtime &runtime) {

/// Raises an uncatchable quit exception.

static vm::CallResult<vm::HermesValue>

quit(void *, vm::Runtime &runtime, vm::NativeArgs) {

- return runtime.raiseQuitError();

+ // return runtime.raiseQuitError();

+ return vm::HermesValue::encodeUndefinedValue();

}

static void printStats(vm::Runtime &runtime, llvh::raw_ostream &os) {

I’ve had some trouble compiling this patch due to a missing cstdint include causing “unknown type name” errors, which were fixed with the following additional patch:

diff --git a/API/jsi/jsi/jsi.h b/API/jsi/jsi/jsi.h

index 08edcd2a0..581d6021e 100644

--- a/API/jsi/jsi/jsi.h

+++ b/API/jsi/jsi/jsi.h

@@ -9,6 +9,7 @@

#include <cassert>

#include <cstring>

+#include <cstdint>

#include <exception>

#include <functional>

#include <memory>

Half an hour later(!!) of compiling on a 16-core laptop, the patched runtime runs the bytecode, and…

$ ./build/bin/hermes main.hbc

The winged thong of Hermes has had a plugger blowout! Can you help him manage his flipflops??

skbdg{fl33t_as_f3ath3rs_and_swift_0f_s0ng}

After I solved this challenge on-venue, the author confessed that she might have accidentally bumped the number of rounds for AES, which was why my previous decryption attempts with the replica script resulted in garbage.

Amending that script with the change that she described, the flag decrypted perfectly. :facepalm:

145c145

< var numberOfRounds = {16: 10, 24: 12, 32: 15}

---

> var numberOfRounds = {16: 15, 24: 12, 32: 15}

$ node ./solve.js

skbdg{fl33t_as_f3ath3rs_and_swift_0f_s0ng}

According to the official solution, the intended solve was patching the bytecode itself to effectively no-op certain false assigns to the global.flipflops variable.

Checking with the author again after the CTF had concluded, it turned out that the AES constant change was an intentional that was forgotten, likely to solve my accidental cheese solve by identifying the bytearrays.

In all fairness, this challenge wasn’t actually hard for me - my ways just led me down a massive rabbit hole, and while I guessed that only a few solves would come for the rest of the competition - given how niche and “weird” the challenge tech stack was - I was genuinely and gently surprised that I was the only solve. gg

Flag: skbdg{fl33t_as_f3ath3rs_and_swift_0f_s0ng}

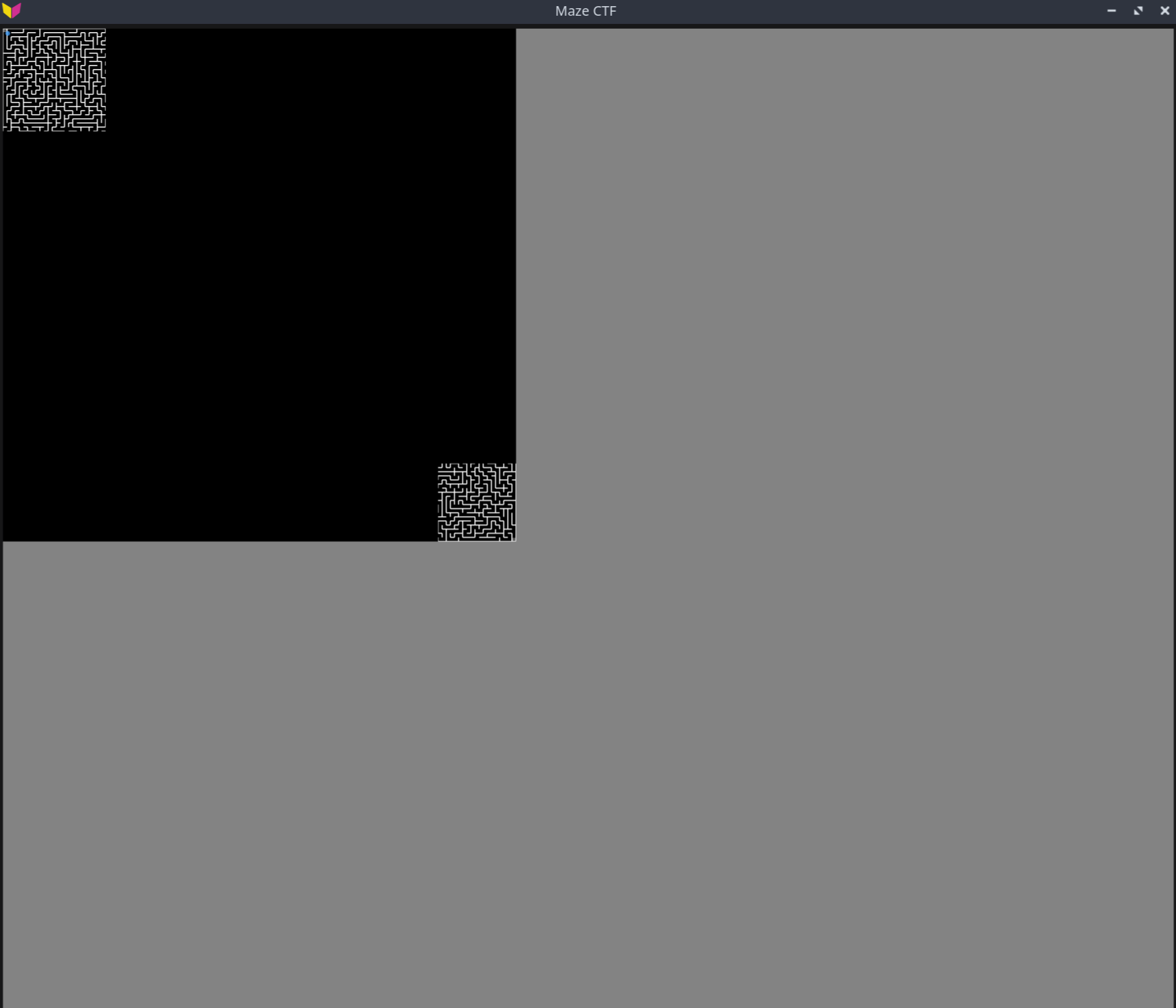

that’s not a maze

This is a maze!

Provided is an unstripped golang ELF binary maze, executing it gives us a maze with some rendering artifacts, likely due to my Wayland setup:

Arrow keys are used to control the little blue dot, which starts you at the top left, and while exploring the maze manually, characters, slowly printed out to stdout were observed, one by one:

$ ./maze

wel

Upon further experimentation, going back and forth on a maze cell which was observed to cause a character to print repeated the same behaviour, meaning that it’s likely that some maze cells had a character mapped onto it, and going directly to the end, also likely at the bottom right.

$ ./maze

wellewwellew

Opening the binary in Binary Ninja and navigating to the actual golang main.main function (@ 0xf1d7c0), I had identified a call to bigmaze/maze/gui.mazeContent (@ 0xf1c7e0), and from some very interesting functions were identified:

bigmaze/maze/gui.decodeMaze@0xf1c480bigmaze/maze/gui.byteToWall@0xf1c3a0bigmaze/maze/gamelogic.positionToChar@0xf1b420

Within mazeContent, there was a memcpy call with 0x3d00 bytes from a bytearray @ 0x17d6df9, followed immediately by a call to decodeMaze. Reading into decodeMaze, the function slices a argument bytearray by 0x7d bytes before further calling byteToWall. In turn, byteToWall has the following decompiled code:

if ((arg1 u>> 3 & 1) != 0)

result = 1

if ((arg1 u>> 2 & 1) != 0)

var_9_1 = 1

if ((arg1 u>> 1 & 1) != 0)

var_b_1 = 1

if ((arg1 & 1) != 0)

var_a_1 = 1

It was time to do some Python experimentation - at the very start of the maze, there is a vertical corridor that is 5 cells. At position (0, 0), the player is only able to go down, but I wasn’t sure if that was due to a wall in the encoded data, or if it was due to bounds-checking. Nevertheless, I started writing a Python script:

raw = [

0x09, 0x0a, 0x0a, 0x0a, 0x0a, 0x0a, 0x08, 0x0a, 0x0e, 0x09, 0x0a, 0x08, 0x0a, 0x0a, 0x08, 0x0e,

...

]

maze = []

for i in range(0, len(raw), 0x7d):

maze.append(raw[i:i+0x7d])

breakpoint()

Experimenting with the bitmask, nothing lined up with the corridor I observed prior, no matter if I indexed it X co-ordinates first or Y co-ordinates first. Looking back at the code, I realised I missed some prior initialisation in mazeContent due to some weird Go quirks and the fact that I didn’t properly define types.

Below is the decompiled pseudocode before my cleanup:

int64_t var_3e95 = 0xa0a090e0a0a090d

int64_t var_3e8d = 0x80a0a0a0a0a090c

int64_t rsi

int64_t rdi

rdi, rsi = __builtin_memcpy(dest: &var_3e8d:1, src: MAZE_BYTEARRAY?, count: 0x3d00)

int64_t* var_50 = &var_3e95

int64_t var_138 = 0x3d09

int64_t var_130 = 0x3d09

int64_t* var_178 = 0x7d

int128_t* rax_1

int64_t rdx_1

int64_t rsi_1

int64_t rdi_1

rax_1, rdx_1, rsi_1, rdi_1 = bigmaze/maze/gui.decodeMaze(rdi, rsi, &var_3e95, &var_3e95, 0x3d09, arg4)

I neglected the fact that it was actually the stack variable var_3e95 passed in, not some previously uninitialised variable, and certainly not var_3e8d, and that already had some bytes pre-set on the stack, meaning I just needed to prepend 9 bytes to my previous Python experimentation script:

raw = [

0x0d, 0x09, 0x0a, 0x0a, 0x0e, 0x09, 0x0a, 0x0a, 0x0c,

0x09, 0x0a, 0x0a, 0x0a, 0x0a, 0x0a, 0x08, 0x0a, 0x0e, 0x09, 0x0a, 0x08, 0x0a, 0x0a, 0x08, 0x0e,

...

]

Now, everything lines up and I had identified the following bitmask:

0b0000

URDL

That is, the 3rd bit set means there is a wall in the Up direction, and so-on.

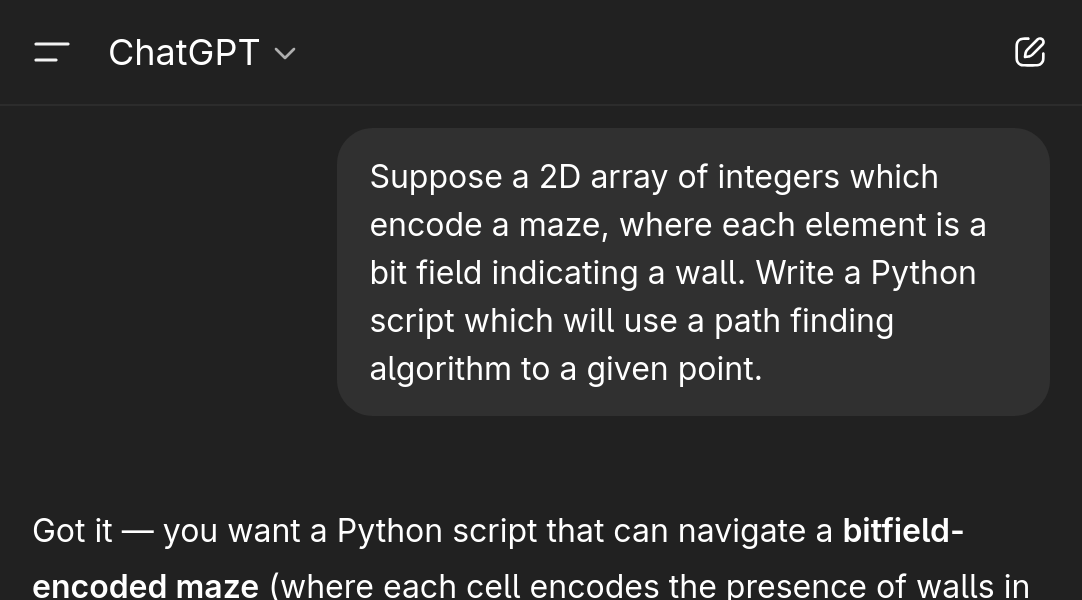

It was at this point the conference was done for the day and competitors had to leave the venue, and were likely heading for the conference afterparty “networking night” at a local pub. It was at this point during the commute that I had no mental capacity or strength to map the bitwise encoding onto some implementation of A* pathfinding, so I asked my best friend:

At the pub, I tested the script with some modifications, and it seemed to find a successful path quickly with just BFS search. Now it was time to find the flag along this path.

The positionToChar function, while very aptly named, also had a giant 0x3d09 byte long array initialised on that stack, likely mapping onto the actual maze the same way as the encoded bitfield array.

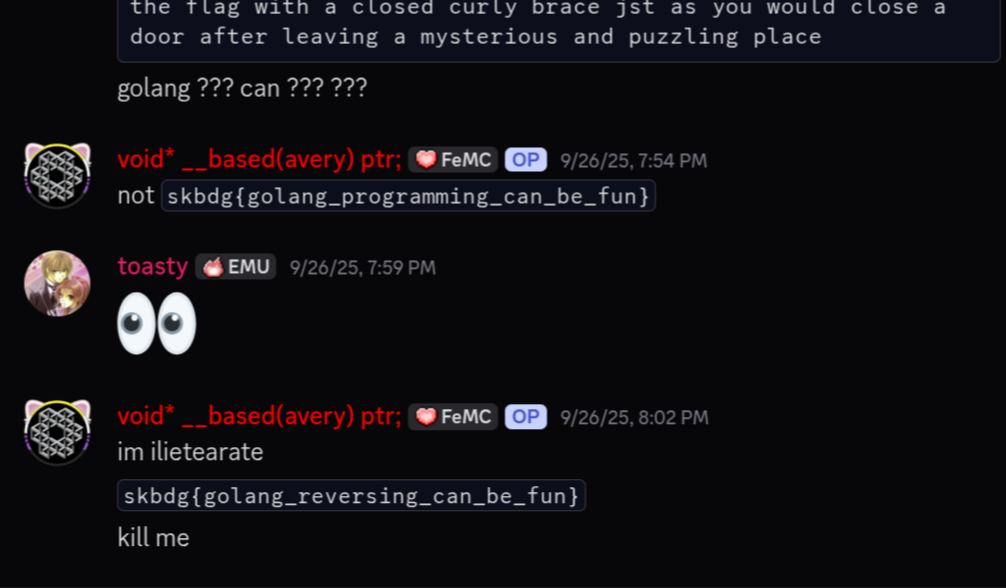

Putting that array into the Python script I had, the maze solve path yielded a long paragraph, courtesy of the author:

welcome to the maze solve this and find the rest of the message. as you step inside you might notice that the walls feel almost endless stretching out in every direction it is certainly and without question a maze and not some other kind of unusual puzzle hidden inside another maze hoc non difficile erit igitur viam invenire potes have you ever noticed how some people always choose the left turn in a maze while others insist on always turning right and both groups are convinced that their method is the best anyway i will describe the flag as you make your way through this maze and i encourage you to pay attention because sometimes details can slip past when you least expect it good luck and have fun as you continue walking and exploring the twists and turns of this place now a small reminder any letters in the flag will all be lowercase and they will consist of several words each one separated by an underscore and i find it interesting how underscores almost look like little paths connecting words together which feels appropriate for a maze of words of course the flag is in flag format and it will begin with skbdg and i promise it is not the short form of skibidi dog anyway that is then followed by an open curly brace and speaking of curly things have you ever thought about how curly vines growing on a wall can look like strange writing from another language next comes a few fun parts of the flag the very first word is golang and while we mention golang it is worth remembering how many people start programming projects with good intentions but end up creating their own labyrinth of code following that the next word is reversing then the third word is can which is simple and short yet powerful with the word after that being be which makes me think of the phrase to be or not to be then the last word of the flag is fun and what better way to finish a journey through a maze than to call it fun and finally you must close the flag with a closed curly brace jst as you would close a door after leaving a mysterious and puzzling place

Granted, at this point I was slightly drunk and kept skimming this prose and skipping over lines, getting frustrated that the flag wasn’t actually there. It was to a point where I gathered that the flag was all lowercase words joined by an underscore, and I thought I had “hints” for the position of only some known words like “golang”, “can” and “fun”; I genuinely thought that the actual flag was in some dead-end path and that I had to amend my search algorithm to keep track of them.

Until I realised that I was stupid.

This was a surprisingly easier-than-I-thought challenge for being the only hard (kickflip) reversing challenge, but I can see how one can get lost in this maze of a binary since this challenge was a GUI game implemented with golang channels and other weird specific stuff. The symbols absolutely helped, but even if the functions were given single character names, the two large arrays would have at least caught some attention, and so would any function referencing the data.

from pwn import ELF

elf = ELF("./maze")

RAW_MAZE = elf.read(elf.symbols['bigmaze/maze/gui..stmp_0'], 0x7d * 0x7d)

RAW_CHARS = elf.read(elf.symbols['bigmaze/maze/gamelogic..stmp_1'], 0x7d * 0x7d)

# 0b0000

# URDL

maze = []

char_map = []

for i in range(0, 0x7d * 0x7d, 0x7d):

maze.append(RAW_MAZE[i:i+0x7d])

char_map.append(RAW_CHARS[i:i+0x7d])

from collections import deque

# Direction mapping: (dx, dy, bit_for_current_cell, bit_for_neighbor)

DIRS = [

(0, -1, 8, 2), # up

(1, 0, 4, 1), # right

(0, 1, 2, 8), # down

(-1, 0, 1, 4), # left

]

def bfs_path(maze, start, goal):

"""

maze: 2D list of integers (bitfield walls)

start: (x, y) tuple

goal: (x, y) tuple

"""

width, height = len(maze[0]), len(maze)

queue = deque([start])

came_from = { start: None }

while queue:

x, y = queue.popleft()

if (x, y) == goal:

break

for dx, dy, wall_bit, neighbor_wall_bit in DIRS:

nx, ny = x + dx, y + dy

if not (0 <= nx < width and 0 <= ny < height):

continue

# check if there is a wall in current or neighbor cell

if (maze[y][x] & wall_bit) != 0:

continue

if (maze[ny][nx] & neighbor_wall_bit) != 0:

continue

if (nx, ny) not in came_from:

came_from[(nx, ny)] = (x, y)

queue.append((nx, ny))

# reconstruct path

path = []

node = goal

if node not in came_from:

return None # no path found

while node is not None:

path.append(node)

node = came_from[node]

path.reverse()

return path

path = bfs_path(maze, (0, 0), (0x7d - 1, 0x7d - 1))

print("Path:", path)

print("".join([chr(c) for c in [char_map[y][x] for (x, y) in path] if c != 0]))

Flag skbdg{golang_reversing_can_be_fun}